Notes

POSITIONING PATIENTS IN BED – NURSING SKILLS

PATIENT POSITIONING

Fowler’s

Fowler’s position is a bed position wherein the head and trunk are raised 40 to 90 degrees.

Fowler’s position is used for people who have difficulty breathing because in this position, gravity pulls the diaphragm downward allowing greater chest and lung expansion.

In low Fowler’s or semi-Fowler’s position, the head and trunk are raised to 15 to 45 degrees; in high Fowler’s, the head and trunk are raised 90 degrees.

This position is useful for patients who have cardiac, respiratory, or neurological problems and is often optimal for patients who have nasogastric tube in place.

Using a footboard is recommended to keep the patient’s feet in proper alignment and to help prevent foot drop.

Orthopneic or Tripod

Orthopneic or tripod position places the patients in a sitting position or on the side of the bed with an overbed table in front to lean on and several pillows on the table to rest on.

Patients who are having difficulty breathing are often placed in this position since it allows maximum expansion of the chest.

Dorsal Recumbent

In dorsal recumbent or back-lying position, the client’s head and shoulders are slightly elevated on a small pillow.

This position provides comfort and facilitates healing following certain surgeries and anesthetics.

Supine or Dorsal position

Supine is a back-lying position similar to dorsal recumbent, but the head and shoulders are not elevated.

Just like dorsal recumbent, supine position provides comfort in general for patients recover after some types of surgery.

Prone

In prone position, the patient lies on the abdomen with head turned to one side; the hips are not flexed.

This is the only bed position that allows full extension of the hip and knee joints.

Prone position also promotes drainage from the mouth and useful for clients who are unconscious or those recover from surgery of the mouth or throat.

Prone position should only be used when the client’s back is correctly aligned, and only for people with no evidence of spinal abnormalities.

To support a patient lying in prone, place a pillow under the head and a small pillow or a towel roll under the abdomen.

Lateral position

In lateral or side-lying position, the patient lies on one side of the body with the top leg in front of the bottom leg and the hip and knee flexed.

Flexing the top hip and knee and placing this leg in front of the body creates a wider, triangular base of support and achieves greater stability.

The greater the flexion of the top hip and knee, the greater the stability and balance in this position. This flexion reduces lordosis and promotes good back alignment.

Lateral position helps relieve pressure on the sacrum and heels in people who sit for much of the day or confined to bed rest in Fowler’s or dorsal recumbent.

In this position, most of the body weight is distributed to the lateral aspect of the lower scapula, the lateral aspect of the ilium, and the greater trochanter of the femur.

Sims’ Position

Sims’ is a semi-prone position where the patient assumes a posture halfway between the lateral and prone positions. The lower arm is positioned behind the client, and the upper arm is flexed at the shoulder and the elbow. Both legs are flexed in front of the client. The upper leg is more acutely flexed at both the hip and the knee, than is the lower one.

Sims’ may be used for unconscious clients because it facilitates drainage from the mouth and prevents aspiration of fluids.

It is also used for paralyzed clients because it reduces pressure over the sacrum and greater trochanter of the hip.

It is often used for clients receiving enemas and occasionally for clients undergoing examinations or treatments of the perineal area.

Pregnant women may find the Sims position comfortable for sleeping.

Support proper body alignment in Sims’s position by placing a pillow underneath the patient’s head and under the upper arm to prevent internal rotation. Place another pillow between legs.

Trendelenburg’s

Trendelenburg’s position involves lowering the head of the bed and raising the foot of the bed of the patient.

Patients who have hypotension can benefit from this position because it promotes venous return.

Reverse Trendelenburg

Reverse Trendelenburg is the opposite of Trendelenburg’s position.

Here the HOB is elevated with the foot of bed down.

This is often a position of choice for patients with gastrointestinal problems, as it can help minimize oesophageal reflux.

Source: Nurseslabs

Discover more from Nursing In Ghana

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Notes

Understanding Hypotension: Types, Causes, and Symptoms

Hypotension, commonly referred to as “low blood pressure,” is a medical condition in which the blood pressure in the arteries is lower than normal (when the blood pressure reading is lower than 90/60mmHg). There are various types of hypotension, each with different causes, symptoms, and treatments. As a nurse, it is important to be aware of the different types of hypotension and their management in order to provide safe and effective care to your patients.

Orthostatic hypotension

Orthostatic hypotension is a type of hypotension that occurs when a person changes position from lying down or sitting to standing up. This can cause a sudden drop in blood pressure, leading to symptoms such as dizziness, lightheadedness, and fainting. Orthostatic hypotension is common in older adults, especially those with underlying medical conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, or autonomic neuropathy.

The management of orthostatic hypotension involves lifestyle modifications, such as avoiding sudden changes in position, staying hydrated, and wearing compression stockings. Medications such as fludrocortisone, midodrine, and droxidopa may also be prescribed to help raise blood pressure.

Neurally mediated hypotension.

Neurally mediated hypotension also known as the fainting reflex, neurocardiogenic syncope, vasodepressor syncope, the vaso-vagal reflex, and autonomic dysfunction is a type of hypotension that occurs in response to certain triggers, such as standing for a long time or exposure to heat. It is caused by a malfunction of the autonomic nervous system, which regulates blood pressure and heart rate. Neurally mediated hypotension can cause symptoms such as dizziness, nausea, and fainting. Other symptoms may include confusion, muscle aches, headaches, and chronic fatigue.

The treatment of neurally mediated hypotension involves avoiding triggers and increasing fluid and salt intake.

Severe hypotension

Severe hypotension is a medical emergency that requires immediate treatment. It is characterized by a sudden and severe drop in blood pressure, which can lead to organ damage and even death if not promptly addressed. Severe hypotension can be caused by various conditions, such as sepsis, anaphylaxis, or a heart attack.

The management of severe hypotension involves identifying and treating the underlying cause. This may involve administering intravenous fluids, medications such as vasopressors or inotropes, and oxygen therapy. In severe cases, mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be necessary.

Postprandial hypotension

It is common in older adults and those with underlying medical conditions such as diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, or autonomic neuropathy. Postprandial hypotension is a type of hypotension that occurs after eating a meal. After eating, the heart rate ramps up to send blood flowing to the digestive system, but with this type of low blood pressure, the mechanism fails, resulting in dizziness, lightheadedness, and fainting.

The management of postprandial hypotension involves eating smaller, more frequent meals and avoiding large meals high in carbohydrates or fats. Medications such as acarbose, midodrine, and caffeine may also be prescribed.

Discover more from Nursing In Ghana

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Notes

SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS (SLE), A COMMONLY MISDIAGNOSED MEDICAL CONDITION

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease that can affect various organ systems in the body. It is characterized by the production of autoantibodies against self-antigens, leading to chronic inflammation and tissue damage including the joints, skin, kidneys, blood cells, brain, heart, and lungs. SLE is a heterogeneous disease with a wide range of clinical manifestations, making it difficult to diagnose and manage.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The pathophysiology of SLE involves a complex interplay between genetic, environmental, hormonal, and immunologic factors. Multiple genetic loci have been associated with SLE, including genes involved in immune system function and regulation. Environmental factors such as infections, medications, and ultraviolet light exposure have also been implicated in the development of SLE.

In SLE, immune dysregulation leads to the production of autoantibodies against nuclear components such as DNA, RNA, and histones. These autoantibodies form immune complexes that deposit in various tissues, leading to chronic inflammation and tissue damage. Additionally, immune dysregulation can lead to aberrant T-cell activation, cytokine production, and complement activation, further contributing to the pathogenesis of SLE.

CAUSES

The exact causes of SLE are not fully understood, but a combination of genetic, environmental, hormonal, and immunologic factors are thought to contribute to its development. Women are more commonly affected than men, and the disease often presents during the childbearing years. Genetic factors are estimated to account for up to 66% of the risk for developing SLE. Environmental factors such as infections, medications, and ultraviolet light exposure have also been implicated in the development of SLE.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The clinical manifestations of SLE are diverse and can affect multiple organ systems in the body. Common symptoms include fatigue, fever, joint pain and swelling, skin rashes, and photosensitivity. SLE can also cause more serious complications such as lupus nephritis, which is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with SLE.

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSTIC FINDINGS

The diagnosis of SLE is based on a combination of clinical and laboratory findings. The American College of Rheumatology has developed diagnostic criteria for SLE, which require the presence of at least four of the following: malar rash, discoid rash, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, arthritis, serositis, renal disorder, neurologic disorder, hematologic disorder, immunologic disorder, and antinuclear antibody positivity. Laboratory tests that may be helpful in diagnosing SLE include antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing, anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibody testing, and complement-level testing.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

The management of SLE involves a multidisciplinary approach, including rheumatologists, nephrologists, dermatologists, and other specialists as needed. Treatment goals include controlling disease activity, preventing flares, and minimizing organ damage. Treatment options may include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antimalarial drugs, glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants, and biological agents.

PHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT

Pharmacologic management of SLE involves a range of medications targeting different aspects of the disease’s pathophysiology. NSAIDs can be used to manage mild to moderate pain and inflammation, while antimalarial drugs such as hydroxychloroquine can be used to prevent disease flares and reduce disease activity. Glucocorticoids such as prednisone can be used to manage severe disease activity and organ involvement, but their long-term use is associated with significant adverse effects. Immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclophosphamide can be used to control disease activity and prevent organ damage. Biologic agents such as belimumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting B-cell activating factor, have also been approved for the treatment of SLE.

Systemic lupus erythematosus diagnosis and management, https://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/article/56/suppl_1/i3/2738661.

C. (2023, January 31). Systemic lupuserythematosus (SLE). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/lupus/facts/detailed.html

Systemic lupus erythematosus pathophysiology – wikidoc. (n.d.). Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Pathophysiology – Wikidoc. https://www.wikidoc.org/index.php/Systemic_lupus_erythematosus_pathophysiology

Discover more from Nursing In Ghana

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Notes

TYPES OF SHOCK

Shock is a threatening life condition of circulatory failure which causes inadequate oxygen delivery to meet cellular metabolic needs and oxygen consumption requirements, producing cellular and tissue hypoxia. The effects of shock are initially reversible, but rapidly become irreversible, resulting in multiorgan failure (MOF) and death. When a patient presents with undifferentiated shock, it is important that the clinician immediately initiate therapy while rapidly identifying the etiology so that definitive therapy can be administered to reverse shock and prevent MOF and death.

There are four main types of shock:

1. Anaphylactic shock

2. Cardiogenic shock

3. Hypovolemic shock

4. Septic shock

Anaphylactic shock is a severe and sudden allergic reaction that can occur after exposure to an allergen. Symptoms include swelling of the face and throat, difficulty breathing, and a drop in blood pressure. Anaphylactic shock can be life-threatening and requires immediate medical treatment.

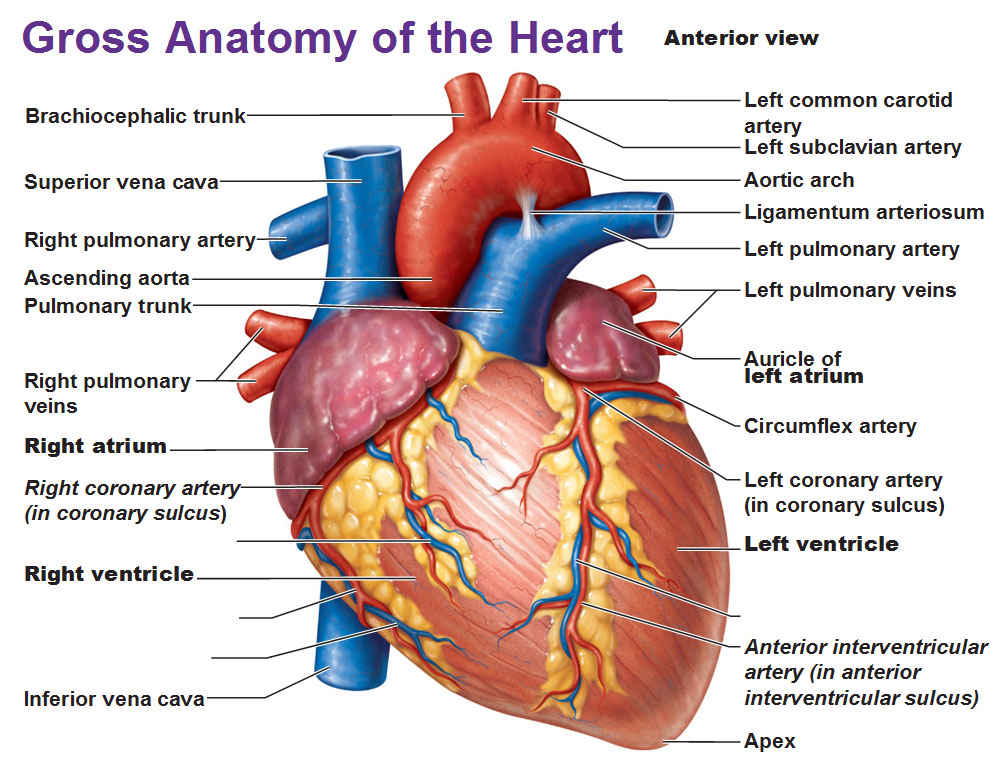

Cardiogenic shock occurs when the heart is unable to pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs. This can be due to a heart attack, heart failure, or other heart conditions. Symptoms include shortness of breath, chest pain, and a weak and irregular heartbeat. Cardiogenic shock is a medical emergency and requires treatment in a hospital.

Hypovolemic shock occurs when there is a decrease in the amount of blood or fluid in the body. This can be due to blood loss from an injury, severe dehydration, or excessive vomiting or diarrhea. Symptoms include lightheadedness, fainting, and a decrease in urine output. Hypovolemic shock can be life-threatening and requires immediate medical treatment.

Septic shock. This type of shock is caused by an infection or sepsis. Sepsis is a potentially life-threatening condition that occurs when an infection spreads throughout the body. Symptoms include low blood pressure, rapid heart rate, chills, and fever. Septic shock is a medical emergency and requires treatment in a hospital.

Discover more from Nursing In Ghana

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

-

Nursing News5 years ago

Nursing News5 years agoLIST OF ACCREDITED GOVERNMENT NURSING AND MIDWIFERY TRAINING SCHOOLS IN GHANA

-

Nursing News3 years ago

Nursing News3 years agoNURSING ADMISSION FORMS ON SALE FOR THE 2023/2024 ACADEMIC YEAR

-

Nursing Procedures and Skills5 years ago

Nursing Procedures and Skills5 years agoTHE NURSES PLEDGE AND THE MIDWIVE’S PRAYER

-

Nursing Procedures and Skills5 years ago

Nursing Procedures and Skills5 years agoNURSING TRAINING ADMISSION INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

-

Nursing News4 years ago

Nursing News4 years agoGHS INTRODUCES TWO NEW BELT COLOURS FOR TWO NEW LEVELS IN THE NURSING AND MIDWIFERY SERVICE

-

Nursing News4 years ago

Nursing News4 years agoMOH SUSPENDS THE 2021/2022 ACADEMIC CALENDAR FOR NURSING AND MIDWIFERY SCHOOLS

-

Notes5 years ago

Notes5 years agoCOMMON TYPES OF INTRAVENOUS (IV) FLUIDS AND THEIR USES

-

Nursing News5 years ago

Nursing News5 years agoLIST OF PRIVATE NURSING AND MIDWIFERY TRAINING SCHOOLS (ACCREDITED)